| Viewer discretion advised. Themes include violence and personal injury. |

Our lives can change in an instant. A fall. A diagnosis. A phone call.

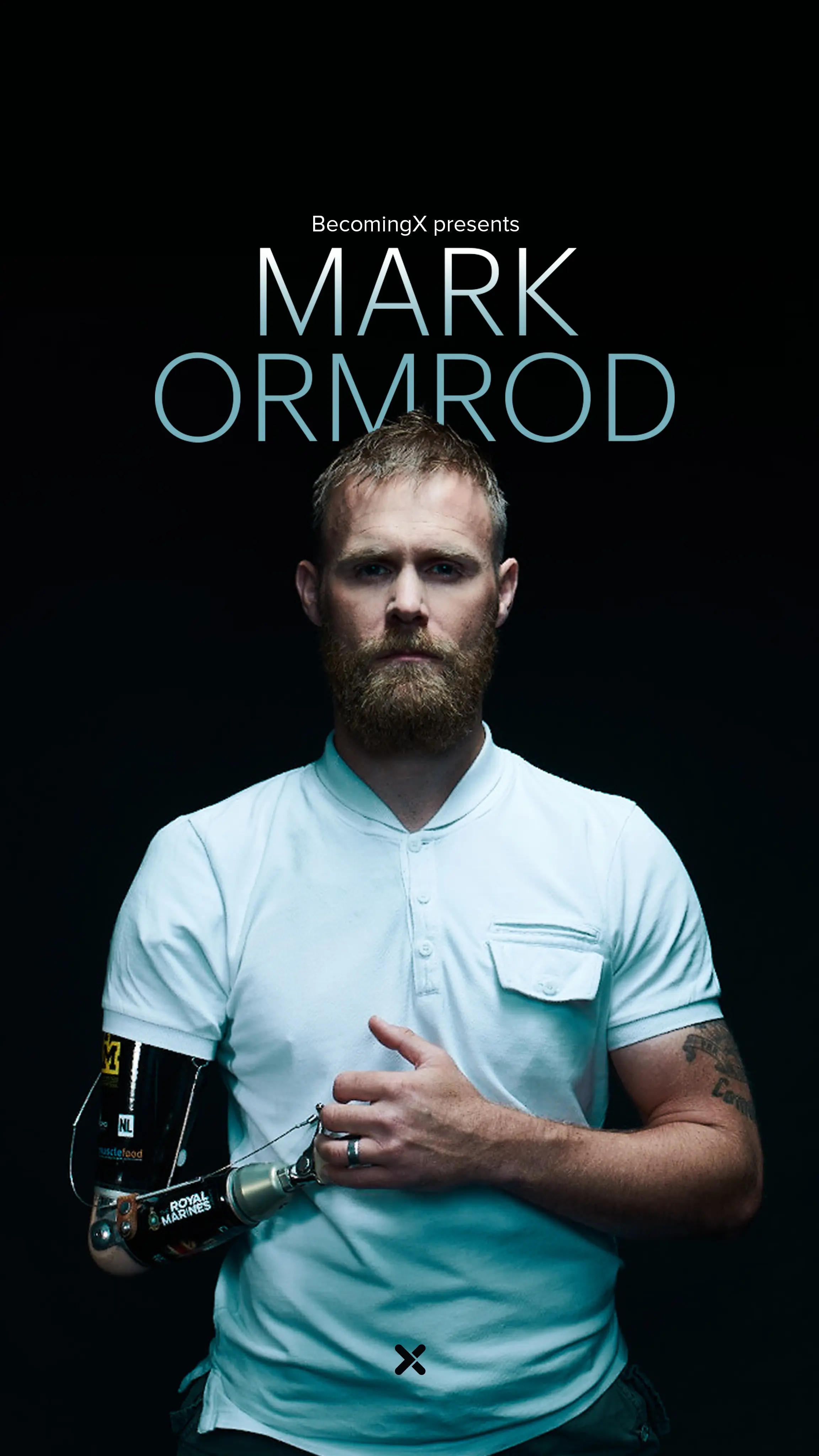

For Mark Ormrod, it was when he knelt on an improvised explosive device whilst serving as a Royal Marine in Afghanistan in 2007. One second, he was on a patrol, the next he had suffered catastrophic injuries that resulted in him losing both his legs above the knee and his right arm at the shoulder. A life changing injury from which he was lucky to survive.

Stories of incredible bravery and survival rarely reflect the harsh realities of those who lived through them. We often like to ignore the darker truth. After his repatriation to the UK, Mark endured unimaginable mental and physical pain. He lay in bed for weeks, suffering from the emotional impact of what had happened and questioning whether he could carry on. He was told at just 24 years old that he would spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

Ormrod’s rehabilitation was not the result of an unquestioning and indomitable mindset, as we so often like to ascribe to others. That came later. The journey began by confronting his darkest visions of the future; a hard-won battle that taught him that he could adapt, and he could learn. He set out to make the very best of his life, no matter what challenges he faced. It was only then that his ‘no-limits’ mindset was really born.

Just fourteen weeks after his triple amputation, Ormrod walked across the parade grounds on new prosthetics to collect his Operational Service Medal. He has been independent of a wheelchair since 2009. In 2010 he ran 3,563 miles across the US in a relay event which took him 63 days. He has hand-cycled around the UK. He has won a total of 11 medals in the Invictus Games, including four gold medals.

Trauma and tragedy can impact us all. The only choice we have is how we respond.

Mark Ormrod – video transcript

I didn't really want to achieve anything as a teenager. I didn't know what I wanted to do and where I wanted to go in my life. So I went down to the Armed Forces Career Centre. I spoke to the recruiting Sergeant down there and I was just like, "This is it. These are the ultimate, all around, go anywhere do anything soldiers. This is what I want to do."

2003, I was called up to go and serve in Iraq on Operation Telic One. And I didn't really do anything for three and a half months. And I came home from that deployment, got a little bit deflated. So the deployment to Afghanistan was the complete opposite end of the spectrum. Constantly, day in day out, fighting in one form or another.

And for the first three and a half months, we were dominating the ground, we had no casualties or anything like that. And then on Christmas Eve we were told to patrol the immediate perimeter of the camp, meet at the front entrance, secure the location, close things down, finish off for the day. The guy in charge, Corporal Helsby, took half of the section and started giving them fire positions. I went to get down to my stomach, and as I put my right knee on the floor, that was the minute that I knelt on and detonated an improvised explosive device.

Inside, everything's going at 1,000 miles an hour in my head, but outside, everything's almost in slow motion. I look down to where my legs should have been and they've just both been completely ripped off, from the knees down. It was a very surreal experience. I don't understand what I'm looking at. My brain couldn't process it, especially because I wasn't in any pain. I swept the floor with my eyes to go back to my legs, just to make sure that what I saw initially was actually true. As I got to about the three o'clock position, I saw my arm just lying there in the sand. My hand was still in pretty good order and I don't know why, but I kind of picked my own hand up, my right hand, and looked at it, and I moved it around a little bit in front of my face and then just dropped it in the sand and just let out this huge scream. Everything hit me at once. The severity of the situation, what had happened and what the likely outcome was going to be. So I just closed my eyes and waited to die.

I could hear the loose rock and everything crumbling as this medic was scrambling up this high feature to come and get me. I have no idea how he got me, out of a crater, off this high feature, down to where the vehicle was waiting, but he did an amazing job. They then flew me back to Camp Bastion, where the field hospital was. And they made the call that the only way they were going to be saving my life is if they amputated both my legs above the knee and my right arm above the elbow.

And one of the things that really got me through it was saying to myself, in the tough times, in those first couple of weeks, "You're still a Royal Marine." Eventually, I rode past this full length mirror, and I stopped. And I looked at myself and I just burst out crying. And I just looked horrible. And I spent that entire night with Becky in that bed just crying, just telling her, I didn't want to do this. I didn't have what it takes. I couldn't do it. It was too much. I want my old life back. I had the, "Why me?" moment. "Why has this happened to me? It's not fair." So that hit me pretty hard.

Five weeks after I was injured, a doctor came in my room. I was told that he was the country's leading medical professional in the field of amputations. And very matter of fact said to me, "I'm sorry, Mark, but you're going to have to start preparing yourself for life in a wheelchair. I have never met anybody in my vast experience who's got just one leg missing above the knee that has any success with prosthetics." Now I was 24 years old at the time, for the next 60, 70, 80 years of my life, I was going to be in a wheelchair and I didn't want to hear that.

And I came across a guy in America called, Cameron Clapp. Now in 2002, when Cameron was 15, he was hit by a train. And it took off both his legs above the knee and his right arm pretty much to his shoulder. I watched his videos online and what this guy was doing was phenomenal. Eventually I emailed Cameron, told him my story, told him I thought he was incredible and that I wanted that level of independence that he had. Him and his team, they turned around to me and said, "Listen, you need to come out to America, meet Cameron, train with us. And we'll do everything we can to get you close to where he's at. Oh, by the way, when you come out, you can't bring anyone with you and you have to leave your wheelchair at home." So I considered backing out and I thought, these guys are crazy, I can't travel to the other side of the world without helpers or wheelchairs or any of this stuff that's getting me through my daily life. I need all this stuff. So the 9th June, 2009 came around, got on a plane, landed in Oklahoma City. And I've been independent of a wheelchair ever since.

This journey, since Christmas Eve 2007, it's been a roller coaster and I've had the good fortune of doing some incredible things. Things that I don't think I would've ever had the opportunity to do had this not happened.

In 2010, me and a couple of friends did a big event where we ran across America. We ran from New York to LA, 3,563 miles in 63 days. And more recently, I got to take part in Prince Harry's Invictus Games. I got in in the team in 2018 for Australia. I got four gold medals in total, two bronzes and a silver. That marked the final part of my rehab. For me, it was kind of like, I'm independent now. Over these 10, 11 years I've done everything that I really wanted to do, that's it I've ticked that big box, rehab complete. I couldn't have asked for a better experience.

My advice to anybody who wants to live up to their full potential is to get yourself around some really good people. People that tell you, "You can do this. You can do that." And they want to empower you and motivate you and inspire you and push you. It doesn't just open your mind, it opens up doors for you too, when you adopt that kind of attitude. I had an idea of where I wanted my life to go, had I have come back from Afghanistan in one piece. And it might have gone that way, it might not have gone that way, but whether it did or whether it didn't, I wouldn't be sat here now, I wouldn't have three beautiful healthy children, potentially not have married Becky. I wouldn't have had the opportunities that I've had because a lot of opportunities come from this. It's given me and my family an incredible life. And yes, it can be rough at times, but so can anyone's life. It's all about mindset and how you deal with that and how you look at these challenges that determines how you're going to make the best of it. So, no, I don't think I'd change a thing.

END CARD

Mark Ormrod became a four time Invictus Games Gold medallist.

Just fourteen weeks after his triple amputation, he walked across the parade ground on new prosthetics to receive his Operational Service Medal.

Defying all medical expectations, he has completed multiple extreme physical challenges to demonstrate what is possible with the right mindset.

He has not used a wheelchair since June 9th 2009, a day he refers to as his 'independence day'.