“Your circumstances don’t define you. They don’t determine where you end up, only where you start from.”

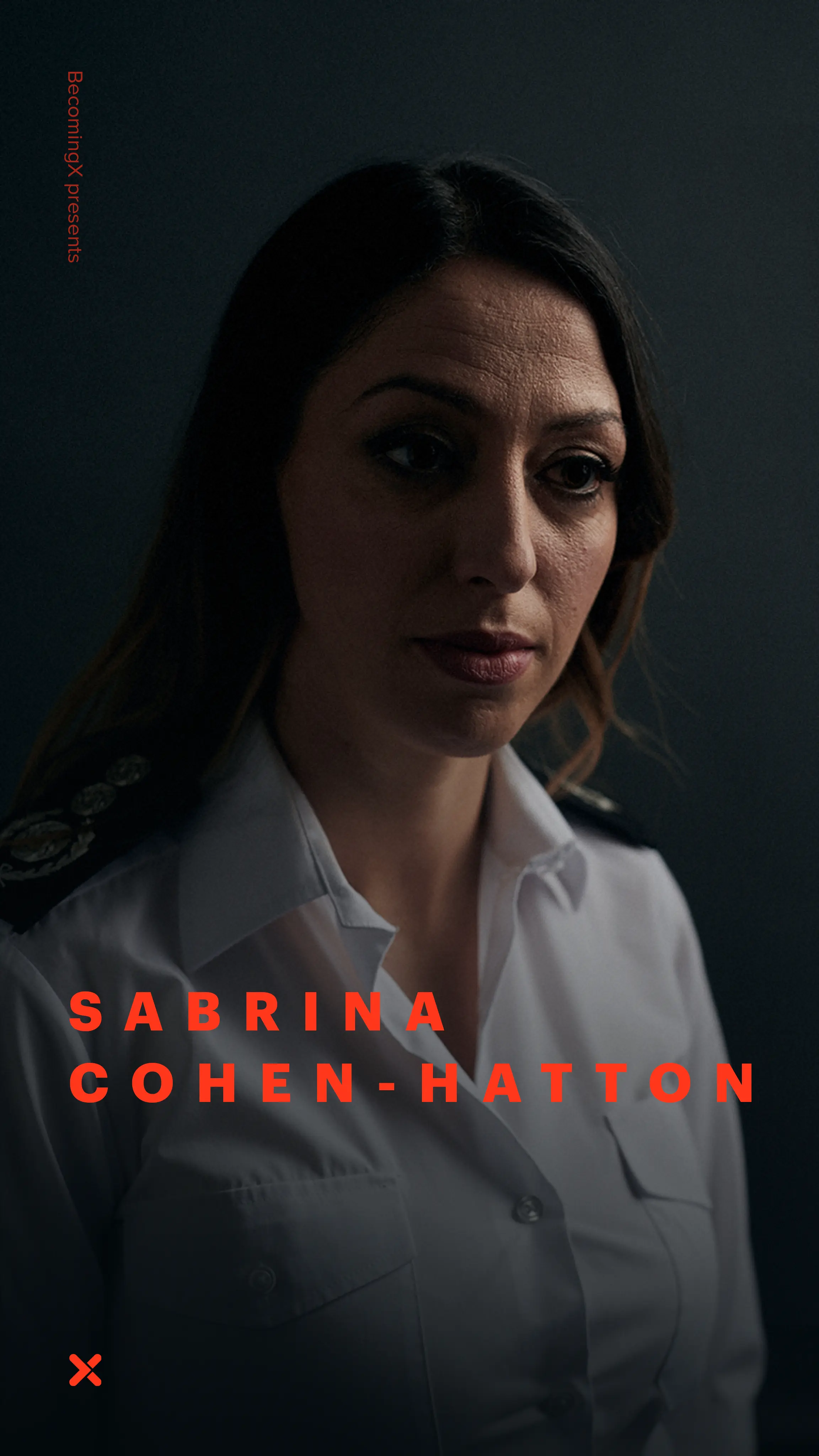

Sabrina Cohen-Hatton found herself homeless at just 15 years old. Hungry. Beaten up. Eating out of bins to survive. Now she’s a Chief Fire Officer; the highest rank a firefighter in the UK can achieve. Her journey is nothing short of extraordinary.

Sabrina lost her dad to a brain tumour when she was just nine. Her mum struggled to cope and after spending time cold and hungry for many years life got even tougher when she found herself sleeping rough on the streets at just 15. What truly stuck out to Sabrina was that nobody cared. People would walk past like she was a ghost, and her own teacher even crossed the road when she made eye contact. Nobody was coming to rescue her. She had to rescue herself.

Sabrina clung to her education, attending school despite her circumstances, and selling copies of ‘The Big Issue’ magazine to try and earn some money. Despite several failed attempts, she continued to persevere and eventually got herself off the streets.

Then came the next chapter of her story. The fire service. Sabrina never had a childhood dream of becoming a firefighter or anything like that. Instead, she wanted to rescue people on the worst day of their lives; in a way that she never had been.

At 5’1” and female, she didn’t fit the image of what most people envision a firefighter to be. She was the first women at her station, in her division, and experienced judgement and harassment repeatedly. But that didn’t stop her. She pushed herself, got better each day, and eventually made it to Chief Fire Officer.

Sabrina’s journey teaches us that it’s ok to fail, just make sure you get back up. Don’t listen to the people who tell you you can’t; do it anyway. Most importantly, own your history. Your circumstances don’t define you.

Sabrina Cohen-Hatton – video transcript

Your circumstances don't define you, they don't determine where you end up, only where you start from. I've gone from living in abject poverty and sleeping rough at 15, to achieving the most senior rank in the fire service at 36. A lot has happened in a very short space of time.

Life growing up for me was tough. My dad died when I was nine years old. He died of a brain tumour. Things got really difficult, and my mum found it really hard to cope. She had a breakdown, and we lived in abject poverty. Physically, life was hard. We were constantly cold. We were constantly hungry. It was a struggle day to day, just to survive. We broke down as a family completely, and I ended up sleeping rough.

As a 15, 16 year old girl sleeping rough on the streets of Newport, it was really tough. I'd often sleep out on the streets, shop doorways, subway tunnels, that kind of thing. I've been beaten up more times than I care to remember. I've woken up with drunk people urinating on my sleeping bag. I was attacked once for being Jewish because he saw my very Jewish surname emblasoned on one of my school books. I thought he was going to kill me that day, he really, really went to town.

There were times in my life where I was so hungry, that I was forced to eat out of bins just to survive. You feel so humiliated, because people are looking at you with disgust. And it's the most dehumanising experience. But a huge part of me thought, “No, no, I need to eat, I'm starving." And when you're sleeping rough, or you're sitting on the side of the street, people walk past you, like you're a ghost, like you're not even there, like they don't even acknowledge your presence. And in fact, one teacher made eye contact, looked down and then crossed the street to avoid me. And it was at that point that I knew that nobody, actually nobody cared. So my choice was to do something about it. And it was to work as hard as I could, for as long as it took to be able to change that situation.

One thing that was important to me at the time, though, was to carry on going to school, I just stuffed my uniform in the bag, and I'd be sleeping out in whatever I'd be wearing. And then I would go in the bus station toilets, and I'd get changed. And then I'd go and I'd get the bus. And then I discovered a magazine called "The Big Issue", which is a street magazine. In those days, you'd buy it for 50p and sell it on for a pound. That enabled me to work my way out of the poverty that I was experiencing. So it gave me some stability, and it gave me some control. And after a while, that meant that I could save up enough to earn my way out of poverty.

Getting off the streets is not easy. It's not as simple as get a roof over your head and that's it. It took me three attempts to escape that life, where I could start afresh, just as me without baggage and without history.

I never had a childhood dream of being a firefighter. It wasn't something that occurred to me when I was growing up. But when I was experiencing homelessness, it honestly felt like every single day was the worst day of my life. And then something would happen the next day and I'd think no, no, that was the worst day, that definitely was. So I know how it feels to be at rock bottom.

Now the amazing thing about fire service, is people trust us to know what to do when they're experiencing the worst day of their lives. So I think in a funny kind of way, I wanted to rescue other people in a way that no one had been able to rescue me.

I first got a job as an on-call firefighter, a part time firefighter effectively, in the South Wales Valleys. And I was the first woman at my station, I was the first woman in my division, and I think initially, not everyone knew how to respond to that. People would regularly say things like, "No offence to you Sab, we just don't agree with women in the job, women will get firefighters killed." And that kind of idea that just because of the package that you come in somehow defines what you're capable of and how good you be, because you don't fit the image, is something that's really frustrating.

I experienced sexual harassment more times than I care to remember. And I've been told that things have to be different for me because I'm not a bloke. Looking past those, I also had some amazing experiences and I've been able to push myself to do things that I never thought that I was capable of. And that's the most important thing.

When I started to look into the fire service, and I suggested it to people, they laughed at me and they all said, "You're too small, you'll never be a firefighter." But I carried on anyway. As I've progressed in my career, I moved from the trucks, from firefighting through to a command role. I'm one of only six women in the country to be a Chief and it's the highest rank that you can get. I think to get there, it takes the ability to fail repeatedly, and still get back up and still carry on, and try again and try again. There are going to be people who will tell you, "You're never going to achieve it," but if you know you can, and if you have a passion to do something, do it anyway.

I definitely don't think that I would be where I am doing what I'm doing, if I hadn't been through those experiences. It is my history, regardless of how palatable it is, being open about that and being honest about being vulnerable, and owning those vulnerabilities has been incredibly powerful. So although I don't want anyone else to go through it, I don't think I'd change a thing now.

END CARD

Sabrina Cohen-Hatton became a Chief Fire Officer, the highest rank a firefighter in the UK can achieve.

She spent two years living on the streets as a teenager, before joining the Fire and Rescue service at just 18 years old.

Having obtained a PhD in behavioural neuroscience, her award-winning research on reducing human error has enhanced safety standards across the UK emergency services.

She continues to try and rescue people, in a way that no one rescued her.