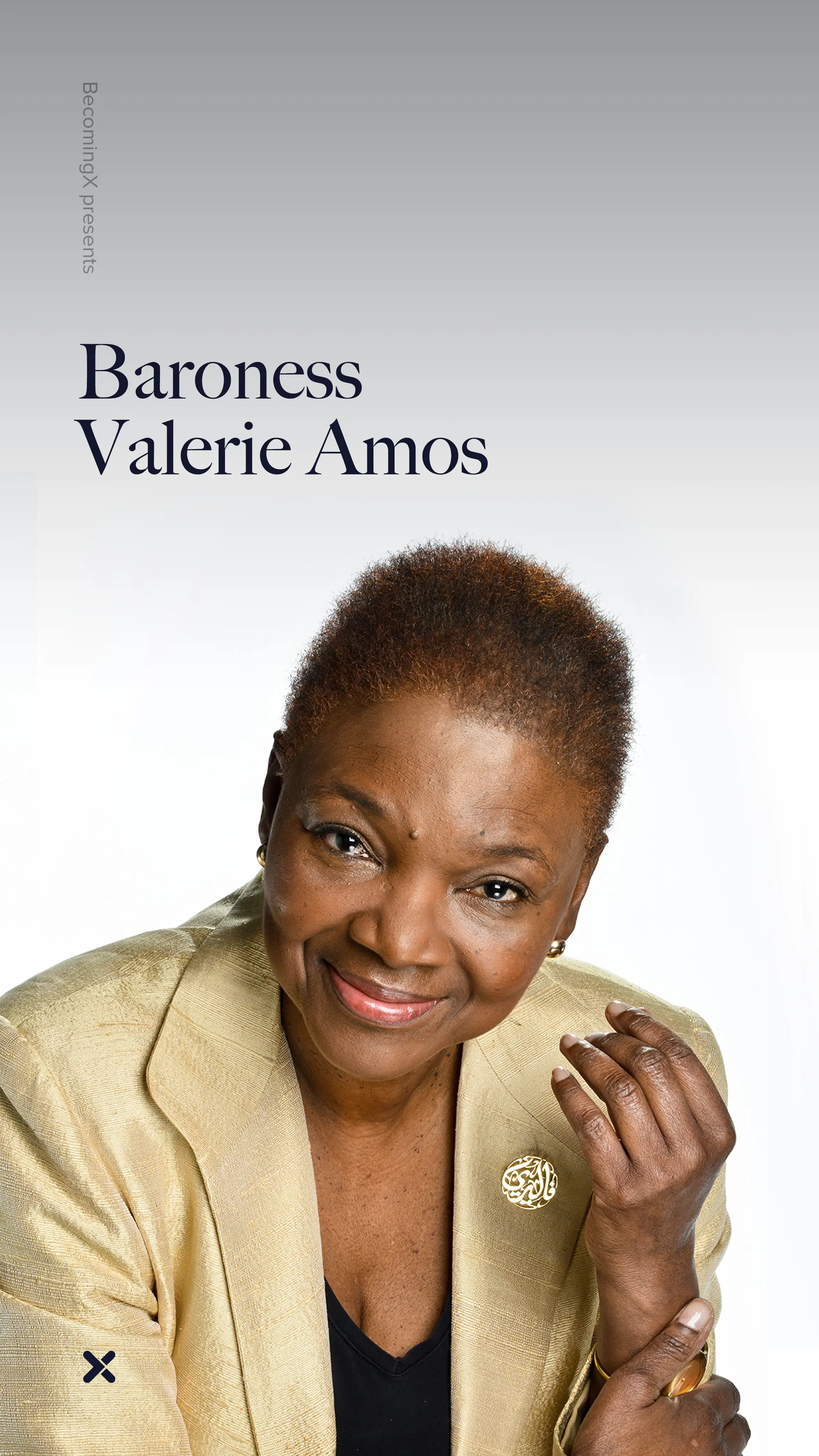

Born in Guyana, South America, Baroness Valerie Amos spent her early childhood in a household where family life, community, and education were paramount. Both her parents were teachers and instilled in her a belief that if she studied hard, she could be whatever she wanted to be. Little did they know she would go on to make history, becoming the first black woman to serve as UK Cabinet minister, and so much more.

Valerie’s move to the UK happened at just nine years old and immediately differences in culture were prominent. Along with her sister she was the first black child in her primary school and even as she got older, she often found herself as the first or only, with regards to her gender, ethnicity, or both. This often brought its own set of challenges.

Valerie didn’t let this set her back though. Quite the opposite. Where she faced knock-backs, she focussed on where she should challenge. She turned those moments into learning.

Throughout her career Valerie has held a series of high-profile positions, including Leader of the House of Lords, Secretary of State for International Development, British High Commissioner, and an Under-Secretary-General for the UN. In 2015 she became the first black woman to lead a UK university and in 2020, the first black head of a college at the University of Oxford.

Despite what one may assume, Valerie is a naturally shy person and had to teach herself how to behave in group settings in order to network effectively. She found this incredibly challenging, but with practice it came more easily.

Underlining Valerie’s ethos is this sense of openness. She encourages people to be more open to new cultures, ideas, identities. To look at things from different perspectives and test personal stereotypes. To face the fear of failure head on and make a change.

Valerie Amos – video transcript

When you're living your life, you're not actually thinking about the fact that you're first.

I remember when I was introduced into the House of Lords, and then when I became leader of the House of Lords, I mean, there was so much pride that this had happened. But my ambition has always been, not so much about myself, but about the kind of work that I do.

I was born in a country called Guyana, it's the north coast of South America. It was a childhood that was very much focused around family life, community, education was a huge thing. Both of my parents were teachers. My father was obsessive about facts and evidence. You couldn't just bring an emotional argument to the table. So, there was definitely that sense in our household that you had to be able to argue your case, and if we studied hard and if we really paid attention to education, we could be whatever we wanted to be.

We left Guyana when I was nine years old, my father had left when I was seven, he came to the UK to study. It was a very, very different culture and climate. I was the first black child in my primary school with my sister.

Being at school and being in the choir, this is when I was in my early teenage years, and we used to go at Christmas time to sing in, what were then called, old people's homes. The residents would always want to touch my skin and touch my hair. They might have seen black people on television but they had never met a black person.

As I was growing up through my career, being in rooms where I would walk in I'd be sometimes the only woman, sometimes the only black person, sometimes the only black woman. So, of course, I have faced issues around my gender and ethnicity through my life. One of the experiences I have is when I went for my first job in local government, which was a race relations advisor. The very last interview was with councillors. It was in a huge council chamber room in Lambeth Town Hall, and all of the councillors they were all white men, sat around in a semicircle at a table. And they had put the chair, sort of, halfway down the room for the candidate, nowhere to put your handbag or anything, and I remember coming in and looking at them all and saying "this is very equal opportunities, isn't it?"

What I do feel now is that every one of those knock-backs, I didn't focus on them in terms of me being the problem, which can be quite easy to do when they happen regularly, as they do. But I really focus on where should I challenge? And turn those moments either into learning for myself or into ways in which I could use them for learning at a later stage.

I remember when I decided to leave government, Gordon Brown was coming in as Prime Minister, and he nominated me for a role within the European Union. I went for it. I was not successful. I went on from that to become High Commissioner in Australia, and indeed was plucked out from that role very quickly, within a year, and asked to go to the United Nations.

One of the most important things that I learnt is that you have to face the fear of failure. There are opportunities that can come out of things that are perceived as failures as well.

Nobody believes this, but I'm actually quite a shy person I have a lot of learnt behaviour in terms of how I behave, how I network. And I had to learn that I would go into a room, and either I could go and hide in the corner or I could go and talk to people. So I used to take a deep breath and just walk up to the first person and stick my hand out and say, "I'm Valerie Amos."

We have to overcome sometimes the ways of behaviour that are natural to us. It's not easy I would not pretend to anybody that it's an easy thing to do, but keep practising.

Being in education now, the things that I hope students take away is an openness to other cultures, to other identities, to other ways of looking at things. Explore and push the boundaries of thinking, but also test personal stereotypes. It's about opening up your eyes and your experience. I want them to feel that they can influence and change the society that they're in.

END CARD

Valerie Amos became the first black woman to serve as a UK Cabinet minister.

After receiving her peerage in 1997, she later became the Leader of the House of Lords, before being appointed Secretary of State for International Development in 2003.

Following her roles as a British High Commissioner and an Under-Secretary-General for the UN, she has continued to achieve new firsts.

In 2015 she became the first black woman to lead a UK University, and in 2020, the first black head of a college at the University of Oxford.